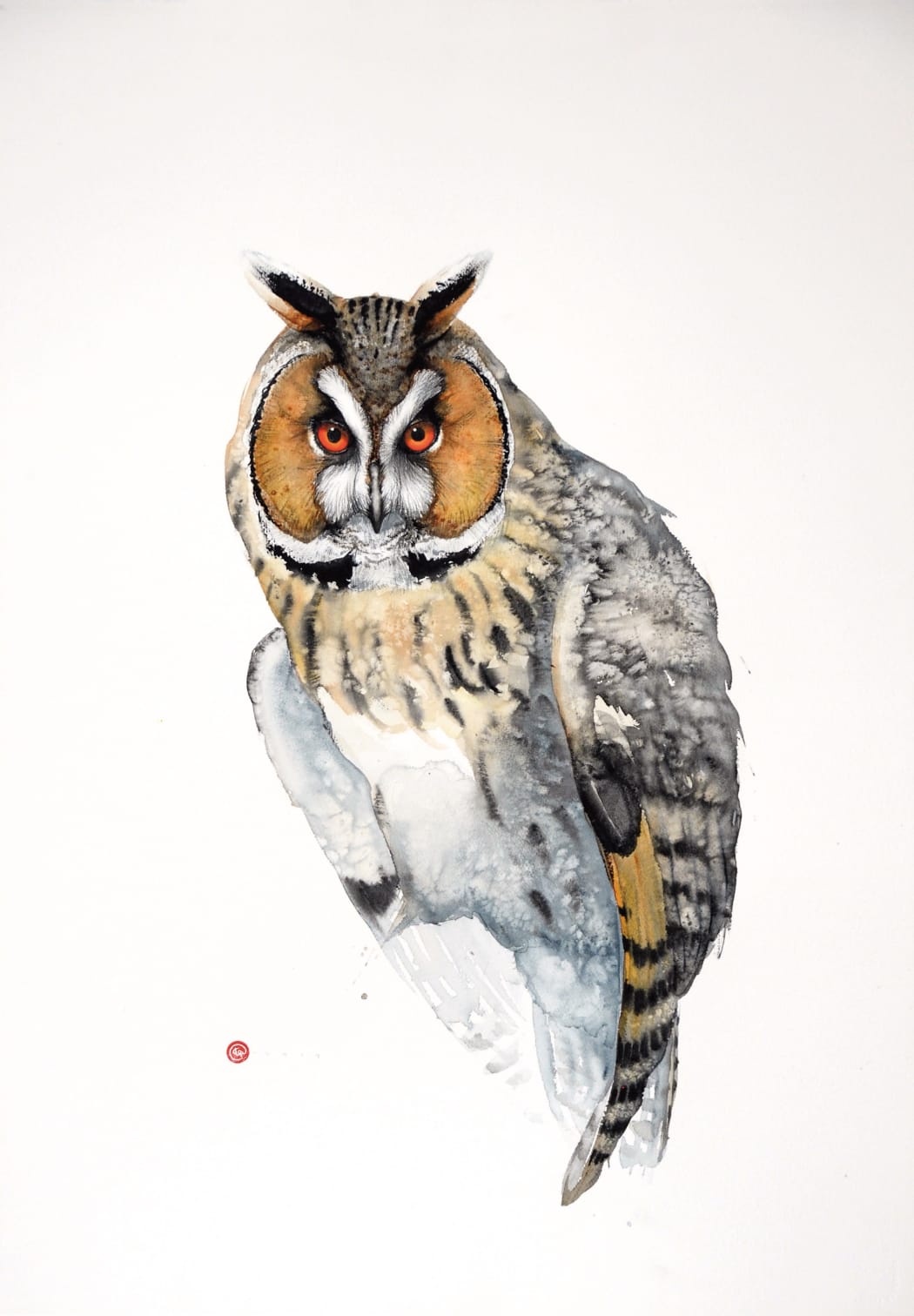

With an exceptional talent for painting birds, Karl Martens adheres to an idea first mooted by Qing dynasty artist Shih T’ao (1642-1707) who believed that the first brushstroke, the ‘holistic brushstroke’, was of huge importance in that it created something where nothing had been before. Martens (a follower of Zen Buddhism) suggests that “the best result is achieved when no thought is given to it, when the mind rests in emptiness and intuition takes over”. Painting almost entirely from memory, with large Chinese and Japanese calligraphy brushes on hand-made paper, Martens works quickly in watercolour - thereby maintaining a freshness and immediacy to his paintings.

Before becoming a full-time artist in 2010, Martens ran a design firm in Stockholm having previously worked in both Toronto and San Francisco (his birth place). In just under a decade, his paintings have garnered worldwide interest and can be found in private collections across the globe.

Red Kite Flying II, watercolour on Arches paper, 75 x 112 cms

In preparation for his fourth solo show with Cricket Fine Art, Karl - with his characteristically calm disposition - was kind enough to answer a handful of questions:

You have a long-standing fascination with birds but can you remember a time when you were painting something different?

Even though it’s hard to remember a time when I didn’t paint birds, I know that I started out painting all kinds of animals. I stayed away from horses though as my mother was best at those and, no matter how hard I tried, I could never “compete” with her. As a kid I loved to copy Disney cartoons and was also interested in exotic flowers, butterflies and landscapes. During my four years at art school I really loved life drawing and, prior to that, I had studied to become a medical illustrator drawing corpses. So, I guess I’ve actually tried most things.

Are some birds easier to capture on paper than others and are there any particular birds that you have yet to paint?

I don’t know for certain whether some birds are easier to depict than others, however I do feel that some are much more difficult. They can often have a very particular expression and even the slightest change of proportion and placement of an eye and a beak, for example, will ruin it. I can try again and again and not get it right; the robin is one of those as I find it’s so easy to lose that mixture of cuteness and toughness they express.

I have a number of birds I would like to paint, for example many birds-of-paradise. However, to most viewers these would look like fantasy birds and I have learned that people like to feel some sort of connection to the bird. As I frequently exhibit my work, and hope that people will feel an affinity towards what they see, I find that all other birds take precedence.

Can you elucidate as to how Zen Buddhism helps your work along with the Japanese archery Kyudo that we understand you practise?

Kyudo trains you to dare to release your aim for the target, to concentrate on breathing and to trust your intuition. It is referred to as “mushin” in Japanese, “no mind” in English or “emptiness” in Zen-speak. You try to be in the present moment, focusing only on the now and not what is to come or has been. Ultimately, you may stand with a fully drawn bow, 30 yards away from a 14-inch target with no desire to hit it. If you can allow your mind, body and bow to harmonise, you will hit the target naturally – given that you will have been practising for many, many years.

I cannot admit to having achieved this in Kyudo but it is a very good way to describe my painting process. It also fits well with the Zen philosophy of letting go of the mind’s tendency to dwell on feelings of doubt, fear of failure, and the desire for things to be a certain way. Therefore when I paint, I try to shut down my intellectual process regarding the image, focus on my breathing and rely upon my intuition – following the brush rather than telling the brush what to do.

Kyodo is much more difficult as, in my mind, I am faced with the “hit or miss” notion and also a greater physical effort. In painting, the “target” is much wider, in the sense that even if the end result is not quite how I imagined, it can still look pretty much like the bird I set out to paint. Thankfully, the notion of success or failure is not as distinct.

Have you always painted with the slightly unusual combination of watercolour and calligraphy brushes and can you tell us about a culinary ingredient that you sometimes use when painting?

For nearly 50 years I was caught up with the minute detail, using pencil and watercolour with regular western brushes; it could take up to a fortnight to paint a bird. And then, in 2001, after attending a workshop in Zen calligraphy with my teacher Alok Hsu Kwang-han, and having begun to understand my own compulsion to control my life, I began to change the way I painted. Using Asian calligraphy brushes I was forced to lose control as the brushes are not really compatible with either watercolour paint or paper. I also discovered that salt did wonderful things to the watercolour pigment that I had no control over – at times it even resembles downy plumage. The result was astonishing and I actually liked what I had painted. Most of the time, I find that the unexpected results are better than anything I could have planned.

Your birds are invariably full of character and we wonder whether you have a favourite bird to paint?

I love to be able to find the individual character of each bird. Initially, a flock of crows may all appear to be alike however, on closer inspection, you will discover that they are all quite different; some look smart whilst others might appear stupid, some have big “noses” and others small. Some birds will have “bad-hair days” and others exhibit perfect plumage.

In my view, members of the crow family – crows, ravens, jays or magpies have incredibly expressive features. You can have a lot of fun with them. I enjoy the feeling of working on a bird’s face and suddenly stepping away from the painting only to find there’s someone looking back at me. Sometimes it can be the matter of a very tiny detail around the eye for it to change from just a painting to a bird coming alive on the paper.

Finally, if you could spend the day with one artist, either living or dead, who would it be and why?

That is almost an impossible question as there are so many. Dr Chao Shao-An (1905-1998) a painter from China comes to mind as his art relates very closely to mine. His ability to express wonderful character in his subjects with just a few simple brushstrokes is uncanny. His compositions and portrayals are full of an appealing humour. I would love to learn more from Shao-An but also light and expression from Rembrandt, analytical rendering from Leonardo da Vinci, daring to test new ideas from Picasso and the ability to challenge myself against all odds from the Swedish painter Olle Skagerfors (1920-1997). And my new idol is the choreographer and dancer Fredrik “Benke” Rydman (b. 1974) who inspires me to be innovative. The list goes on, and on, and on ...

Karl Martens in preparation for Kyudo (Japanese archery)